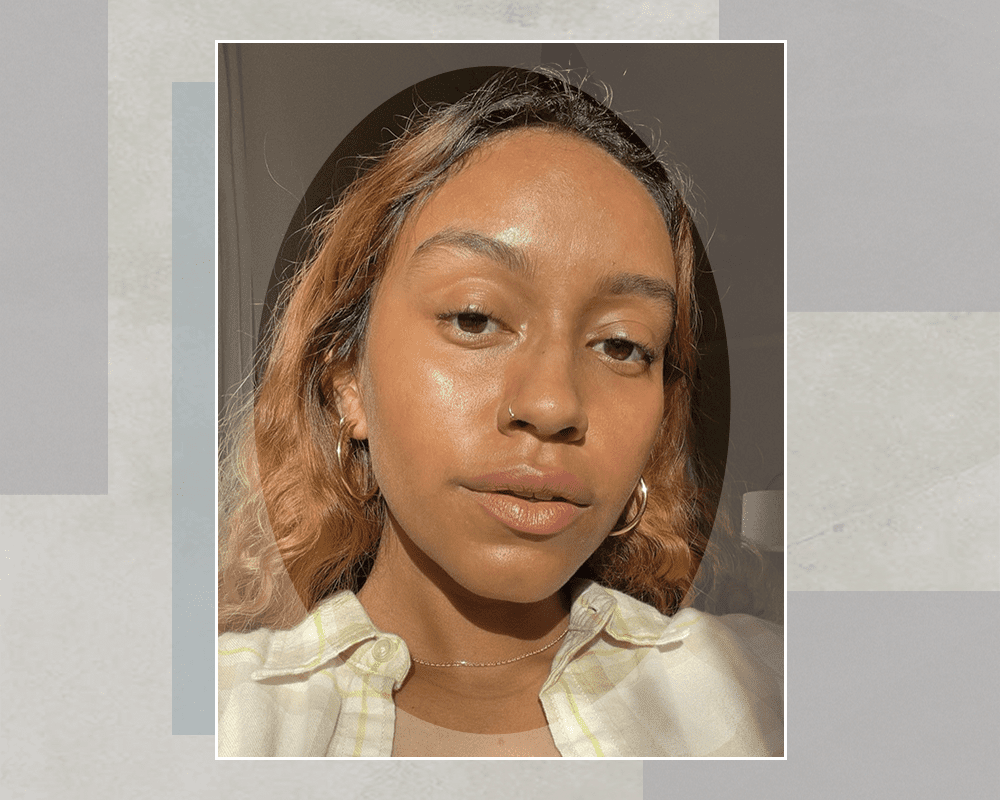

Beauty in its physical form, often insists on itself in the most impractical way. Human beauty standards, once a monolith, never pretended to be a rational set of rules. Whether chiseled in marble, dabbed on canvas, or captured on film, images reflected to the public showcase beauty while telling the viewer they’ll never achieve it. Yet I still whispered in awe at the Louvre while in front of the Venus de Milo, a goddess chiseled into stone.

Back in Georgia a few weeks later, I read an article that declared the statue’s beauty came from the deft work of a master artist, one who understood the golden ratio trait in beautiful people.

What Is the Golden Ratio?

The golden ratio; or, beauty, explained with an equation. An attempt to organize the chaotic impracticality of beauty. The golden ratio is irrational, yet the number shows up everywhere: in marine life (that spiral in seashells), in architecture (The Taj Mahal), microscopy (DNA molecules have big golden ratio energy), and in the entertainment industry (faces).

Simply put, Taylor Swift, Kate Moss, and Scarlett Johanssen, all talented women, are mathematically perfect, according to the golden ratio (sometimes called the Fibonacci sequence), which, when written, looks like this: φ, or (1+ square root(5))/2.

A Real-Life Version of the Golden Ratio

For eight spectacular weeks, Nat* the New Girl took our small Catholic elementary school by storm. She was the same age as me, but unlike me, her mother let her wear makeup and perfume. I slathered my cherry Chapstick before school in hopes it would look like lipstick (it didn’t). Nat slicked on pink, glittery lip gloss during class with long-limbed grace. The other kids wore our uniforms with a quiet complaint, but Nat wore the white shirt, plaid skirt combo with an untucked nonchalance that could never be replicated—no matter how much all the girls tried to emulate her. In my memory, the curly-haired brunette bore more than a passing resemblance to the legendary Marilyn Monroe (mega golden ratio energy, by the wya). Back then, when Nat raised her hand to ask for a hall pass, her eclectic mix of friendship and beaded bracelets clattered from her wrist to her elbow in a display that transfixed boys and girls alike.

By the end of Nat’s first day, every student in our grade had untucked their shirt from their uniform. At the end of the first week, every girl wore an arm full of colorful bracelets. By the beginning of the second week, boys said her name in tones something like awe and disbelief.

To borrow a classic line from the cult movie, To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything, Julie Newmar: You couldn’t describe Nat without using the words classic and beautiful. Couldn’t be done. I wanted to borrow some of that Nat sparkle. I couldn’t have her cheekbones, but maybe I could convince my mother to let me buy Nat’s favorite lip gloss.

“I don’t care if all the other girls wear makeup,” my mom told me when I asked her if I could buy lip gloss the fourth week in a row. I flounced out of the kitchen with tears in my eyes, because it wasn’t just that I wanted to be like the other girls in my class, I craved a classically beautiful face in a way that I couldn’t articulate. The standard of beauty, one that I desperately wanted to attain, slipped out of my reach, again and again. And yet I reached for it, knowing I’d fail every time.

Another way to write the golden ratio is as an infinite, continued fraction: 1+1/(1+1/(1+1/(…))).

If you were to read the above fraction out loud, it would sound like this: “one plus one over one plus one over one plus one over one plus one over…” The point is, you could spend the rest of your life repeating the words, and it wouldn’t matter. You could never fully express the entirety of the golden ratio. You’d never have the perfect answer, although you could try.

What Will We Consider Beautiful Years From Now?

Times change. People change. And with it, standards of beauty change. Winnie Harlow stuns in ad campaigns. Lady Gaga tells her Little Monsters they were born this way. We live in a world with a pinup glam bionic pop star.

Culture accepts more people into the “beautiful and seen” club because we as society demanded it, we protested for it, and, having grown tired of an invitation, we looked beauty’s gatekeepers in the eye and opened the doors ourselves.

And that golden ratio? Mathematician John Allen Paulos says it’s time to retire the notion of a formula for beauty. Paulos disputes the golden ratio altogether, going so far as to say a 5×3 index card meets the golden ratio standard of beauty. Any spiral within a rectangle creates the mathematical equation, and no one is giving an index card a makeup deal. The Twitter account Fibonacci Perfection parodies this persistence of the golden ratio.

So, can you define the perfect beauty? Here’s the answer: Venus de Milo. Marilyn. Nat. You. Me. All of us. Back then and a hundred years from now. No math required.

*Names have been changed.